By: Marisol Maddox, Arctic Analyst, the Wilson Center Polar Institute

The Wilson Center was chartered by Congress in 1968 as the official, living memorial to President Woodrow Wilson. It serves as a key, non-partisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for the policy community. The Polar Institute of The Wilson Center was formed in 2017 and has become a premier forum for discussion, policy analysis, and expertise on issues pertaining to the Arctic and Antarctic.

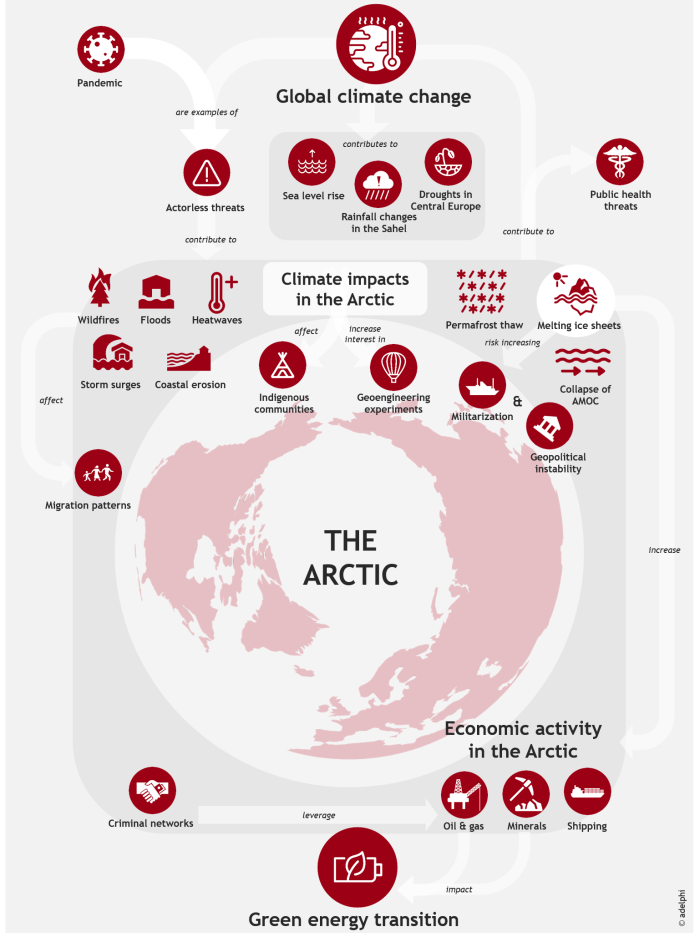

During the summer of 2021, I authored the Climate-Fragility Risk Brief: The Arctic as part of a Polar Institute collaboration with the Berlin-based think tank, adelphi, and their Climate Security Expert Network (CSEN). Climate change is one of several "actorless threats," which will increasingly shape the global threat to the environment and challenge stability. The term, actorless threats, referring to the lack a proximate causal actor, is useful because of the implications it has for the evolution in thinking necessary for policy, security, and intelligence communities to properly frame our changing reality, where significant threats are developing in the form of something other than a state or non-state actor.

These risks are demonstrative of the fact that actorless threats, like climate change, will increasingly influence global stability, both directly as well as indirectly through the ways that state and non-state actors respond to them. For instance, certain geoengineering technologies are relatively inexpensive and accessible, so could potentially be deployed by a wealthy individual. The risks are profound whether or not the intentions are benevolent.

The Arctic is warming three times faster than the global rate of change. Several global climate tipping points are directly linked to changes in the Arctic, namely, the stability of the Greenland ice sheet, the stability of permafrost, and the strength of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which is a giant ocean conveyor belt that contains the Gulf Stream.

There is about seven meters worth of global sea level currently locked up in the Greenland ice sheet, and it is melting from the top down and the bottom up. Research has demonstrated the global climate impacts of diminishing land-based ice from Greenland, such as the established connection between Greenland's ice melt and a "drastic decrease" in west African monsoon precipitation, which impacts the fragile Sahel region of Africa. The gravitational pull of the Greenland ice sheet means its melt has direct implications for the US Eastern Seaboard (Bartelme 2021).

Over 80% of Alaska and 60% of the Russian Federation are underlaid by permafrost and there are significant concerns about implications for critical infrastructure as well as for permafrost's contributions to further warming. When permafrost thaws, it releases methane—an extremely potent greenhouse gas—as well as carbon dioxide. It is estimated there are around 60 billion tons of methane and 560 billion tons of carbon trapped in subsea permafrost, sediment, and soils. Permafrost is also concerning as a source of novel pathogens (ancient viruses, fungi, bacteria), as well as radon and mercury, which are both pertinent to public health. New research takes a novel approach in beginning to catalog a list of biogeochemical impacts of permafrost thaw, making it clear that the implications of Arctic cryosphere degradation are profound (Miner et al. 2021).

The AMOC is the weakest it has been in over 1,000 years due to the freshening and warming of the Arctic Ocean. Increased rainfall, coupled with greater melting of ice, adds significant amounts of freshwater to the ocean. This reduces the salinity and density of the ocean water, which combine with the temperature increase to inhibit the sinking and circulation of AMOC— hence it slows down. If this trend continues and combines with a period of reduced solar activity due to natural variability, the result could be decades-long mega-droughts in central Europe.

It is unclear whether it is possible to overshoot thresholds, by how much and for how long, and still remain safe. There is additional risk that triggering one tipping point may cause other tipping points 'thresholds to be crossed in a domino effect. It is also clear that particularly when it comes to the cryosphere, it is important to limit warming to 1.5°C because once glaciers, ice sheets, and permafrost are gone it "will be essentially permanent on human timescales, and catastrophic for humanity"(ICCI 2021).

The accelerated rate of warming in the Arctic also creates geopolitical and human security risks. China is seeking to establish itself as a stakeholder in the Arctic to gain access and influence, while Russia is increasing its military capabilities and aggressive posturing in the region leading to threat of security dilemma dynamics with neighbors and NATO. Increased access and new commercial opportunities come with a growing risk of opportunistic transnational crime and illicit financial flows, while policy and emergency response mechanisms lag behind the fast-changing reality.

The CSEN risk brief includes several entry-points for action from the policy community, including the need for urgent global action to catalyze emissions reduction efforts and increase carbon sequestration, with an emphasis on nature-based solutions that also seek to support biodiversity and Indigenous communities. Multilateral Arctic military dialogue must be renewed to reduce risk of escalation or misinterpretation. Governance structures should be appropriately adapted to the new Arctic reality to prevent gaps, and the integrity of sustainable development should be upheld through actively limiting opportunities for bad actors to exploit new opportunities, such as fraud in carbon credit markets.

A more involved cultural paradigm shift will be necessary as part of the longer-term work to address the root causes of climate change. At the heart of this matter is the falsehood that humans are somehow separate from nature, as if it does not exist within us, and that it is necessary for humans to dominate nature in order to survive. Nothing could be further from the truth. This illusory falsehood is at the philosophical foundation of many policy approaches that have led to the structural challenges we are confronted with today, and needs to be addressed. Indigenous Knowledge must be at the core of our approach toward seeking solutions. To effectively confront these new risks, it is crucial to balance boldness and urgency of action with humility and acknowledgement of the profound nature of the larger work that must be done in order to be successful.

For further information, please download the Climate-Fragility Risk Brief: The Arctic and the accompanying Factsheet.

About the Author

Marisol Maddox is an Arctic analyst at the Polar Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and a non-resident research fellow at the Center for Climate and Security. Her research interests include the security and geopolitical implications of actorless threats such as climate change and biodiversity loss, as well as international collaboration opportunities, with a regional focus on the Arctic.